Explore our manual for resources on medical debt.

You can view the full contents of the manual below. However we recommend that you download a PDF version of the manual for easier reading and printing.

You can view the full contents of the manual below. However we recommend that you download a PDF version of the manual for easier reading and printing.

If you live in New Jersey, this Manual is for you. It is meant to help you and other New Jersey consumers, whether insured or uninsured, understand what your rights are when it comes to the cost of medical care and the burden of medical debt—to keep you from incurring medical debt in the first place, or help you reduce the amount of it, and to provide advice on how to deal with medical debt collectors and what to do if you are sued over a medical debt.

Even if you currently have no medical debt, and have—or think you have—good health insurance, all it takes is for you or a member of your immediate family to come down with a serious illness or chronic medical condition or be injured in an accident and you might find yourself joining the ranks of the estimated 100 million Americans who owe more than $220 billion in medical debt.* In New Jersey, there are 1.5 million residents struggling with medical debt. We cover topics such as the availability of financial assistance, out-of-network charges (which can lead to surprise medical bills), how to negotiate a payment plan, a new state law that prohibits the reporting of medical debt to the credit reporting bureaus, and what you can do if a medical debt is reported in violation of the law. We even explain the basics of how to read your health insurance card so that you can better understand your coverage, how to properly read a medical bill and when your insurer denies coverage or otherwise fails to pay the appropriate benefits under your policy, how to appeal that denial. And we discuss why you might be better off not using your credit card to pay for medical debt and why you also need to be careful about using medical credit cards like CareCredit or other specialized medical credit cards.

Throughout this Manual, there are links to websites containing additional information or forms which those who use this Manual online or in some other digital form can click on for ready access. For those, who print out the Manual on paper and cannot make use of the hyperlinks, we have provided the URLs (Internet addresses) in Endnotes at the end of each chapter.

The Appendix provides important forms you can use to request an itemized bill, dispute charges with a medical debt collector and respond to a legal case filed against you in court for medical debt. It contains a list of Federally Qualified Health Care Centers in New Jersey, which provide care to everyone, regardless of ability to pay. If you are uninsured, fees are charged on a sliding scale based on your income. There is also information about how to find a lawyer if you need one, and possibly free legal services if you meet the financial criteria.

DISCLAIMER: The information in this Manual is not legal advice. It is a source of information to help New Jerseyans deal with medical debt. For legal advice, consult an attorney.

This chapter is for those who have health insurance of some kind – private insurance through your job or an individual policy bought on an insurance exchange, or through some public program like NJ FamilyCare, Medicaid or Medicare. Any kind of insurance is better than none, but policies differ not just in the monthly premiums you pay but also in: what benefits they provide and the scope of coverage, including the size of deductibles and co-pays; on pre-approval requirements; which providers are in or out of network; and what drugs are covered.

If you have health insurance, you should have an ID card, which contains important information about your plan. This section will help you understand what the card says and what it means or coverage under your plan.

The information contained on the card typically includes:

Here is what the terms mentioned above mean:

Fully-Funded Plans (HMO. PPO, POS)—Most insurers have some sort of limitation on the health care providers you can see and still obtain insurance benefits.

HMO: The most restrictive plans are HMOs or Health Maintenance Organizations where, other than in an emergency, there is generally no coverage if you see a doctor who is outside of the insurance company’s network or not part of the HMO. You will probably have to pay the charge in full for such providers.

PPO: In a Preferred Provider Organization plan, you pay less for providers who are in the insurance company’s network but you can use out-of-network providers without a referral for an additional cost. It is the most flexible type of plan but also tends to be the most expensive.

POS: A Point of Service plan is like a PPO except that your Primary Care Physician (PCP) must provide a referral for any visit to a specialist or out-of-network provider.

Self-Funded Plan: These are plans that are financed by a private sector employer and administered by a health insurance company. They are governed by the provisions of the federal “Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974,” also known as ERISA, and are not regulated by state law.

Government Plans: Medicare, Medicaid, NJ FamilyCare, Veterans Health Benefits, State Health Benefits Program, and School Employees Health Benefit Program

Medicare: The federal Medicare program, which covers people who are 65 or older or who have certain disabilities or conditions

Medicaid: The State Medicaid program, which covers people with low incomes, pregnant women and children.

NJ FamilyCare: A comprehensive, federal- and state-funded health insurance program created to provide income-qualified New Jersey residents, of any age, who do not have employer insurance, with access to affordable health insurance. It includes the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicaid and Medicaid expansion populations.

Veterans Health Benefits Plans: Veterans Health Care and all insurance programs that make up TRICARE, the healthcare program for the U.S. armed services. It covers active duty service members and their families, National Guard and Reserve members and their families; and retirees and their families.

State Health Benefits Program (“SHBP”) and School Employees’ Health Benefits Program (“SEHBP”): The programs cover active state employees and local school board employees and their dependents. Learn more about SHBP here and about SEHBP here.

Deductibles—A deductible is the amount the insured must pay out of pocket before the insurer is required to pay anything and it resets annually so you have to meet it again each year. There are two main types of deductibles—for in-network and for out-of- network care, usually with a separate deductible for each person covered by the plan and for a family plan, a deductible that applies to the entire family. If the deductible has not been satisfied and you incur medical charges, you have to pay the entire amount of the charge until the deductible for that year is reached (although you still get the benefit of any reduced charge that the insurance company has negotiated with the health provider for that particular type of service). Even when you have fully satisfied the in-network deductible, if you incur charges for care from an out-of-network provider, you must satisfy the out-ofnetwork deductible separately. That is a good reason to stay in-network on top of the fact that even after the deductible is met and coverage kicks in, your insurer might cover a lower percentage of out-of-network costs—maybe 60 or 70% rather than 90%, for example.

Co-Pay—A co-pay is a set fee that you pay every time you see a doctor or other health provider or pick up a prescription. It can vary with the type of health care or the type of prescription, ranging from as low as $0 to $50 or more for a regular office visit, but usually higher for a specialist and it tends to be higher still, as much as $100 or more, for an emergency room visit. Your ID card might also specify a co-pay for Urgent Care visits, which are increasingly replacing Emergency Room visits for times when medical care is needed right away for injuries or illnesses that are not serious enough to warrant a visit to the E.R.

Under the Affordable Care Act, or ACA (also widely referred to as “Obamacare”), which became law in 2010, no co-pay whatsoever can be charged for certain types of preventive care, including vaccinations, mammograms and colonoscopies. A major caveat is that if the test is not just being done as part of regular, periodic screening, but to diagnose a suspected illness or condition, perhaps because of symptoms that are present, the testing is no longer deemed preventive and the usual deductibles and co-pays apply.

Co-Insurance (also known as Co-Share)—It is the percentage of a covered expense that a patient pays after meeting their deductible. It is a way for the patient and their insurance provider to share the cost of a service. For example, if the insurer pays 80%, you pay the other 20% (it can be higher or lower depending on your plan) and that 20% share is referred to as co-insurance. If a provider is out-of-network, the insurer might still cover the charges, but usually pays a lesser portion, maybe 70% or 50%, leaving you with a co-insurance obligation of 30% or 50%.

Out-of-Pocket Maximum*—Whether or not it is indicated on your insurance ID card, most plans have an annual out-of-pocket maximum, and after you meet that amount, all of your eligible care should be 100% covered for the rest of the year. Deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance all count toward the out-of-pocket maximum.

Your insurance card will not mention pre-authorization, prior authorization or pre-approval (which are all the same thing) but there will almost certainly be at least some health care services, procedures, providers or prescriptions that require it. If you go ahead and have the service or procedure, see the provider or fill the prescription without such approval, it might not be covered at all. If you are in any doubt about whether pre-authorization is required even if your doctor or the health care facility involved has obtained such approval on your behalf, make sure by calling the phone number for members on the back of your insurance ID card and confirming it for yourself or obtain a copy of the plan itself from your insurer or employer to check what it says. It is also a good idea to confirm whether a particular provider, lab or testing facility is in-network or out-ofnetwork, in order to keep medical costs down. Again, call the insurance company and do not rely on a printed or online directory, which might be out-of-date. The provider, whether a lab, hospital or physician, is supposed to inform you whether they are in-network with your insurance plan.

A new state law, known as the Ensuring Transparency in Prior Authorization Act,

which went into effect on January 1, 2025, provides some protections for the pre-authorization process:

Some people might be covered by more than one insurance policy. Both policies might be coextensive, providing general health coverage. Examples are: a person might be covered by their own employer plan and their spouse’s; children might be covered by both parents’ plans; someone might have both an employer plan and a government-sponsored plan such as Medicare or Medicaid, or both Medicaid and Medicare (known as a Dual Eligible Special Needs Plan or D-SNP). Sometimes, people have supplemental policies that cover expenses for dental or vision. For those with auto insurance, Personal Injury Protection provides coverage for crash-related injuries.

With two policies, one is primary, meaning it pays first and covers a larger portion of the bill while the secondary plan covers remaining eligible costs. Claims processing can be more complicated and there is a coordination of benefits (COB) process to determine which plan pays first and how much.

It is crucial to communicate with both insurers to understand their COB provisions and ensure proper coordination. It is also essential to make sure that your health provider knows that you have dual coverage so that they can seek payment from both and maximize the insurance benefits available to you before sending you a bill for any remaining balance.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, usually referred to more briefly as “The Affordable Care Act” (ACA) or “Obamacare,” was signed into law in 2010 and has been in effect for more than a decade. It is mostly thought of as a law that increased the number of people with health insurance but it did more than that in increasing protections for everyone with health insurance.

Probably the most well-known provisions are those that: allow children under 26 to stay on their parents’ policies; prohibit deductibles or co-pays for preventive care and testing; and bar insurers from denying coverage for pre-existing conditions (such as heart disease, diabetes, asthma, cancer or pregnancy) or charging more or limiting benefits for them.

Essential Care Coverage—The ACA also defines certain health services listed below as essential and requires that they be included in every health insurance policy:

What is a “Surprise Medical Bill”?—A “Surprise Medical Bill” is an unexpected bill from an outof-network health provider or out-of-network facility such as a hospital, clinic or laboratory, that you did not knowingly and deliberately chose to treat you. The “surprise” can come from getting any bill at all because you thought you were covered in full or from getting a bill that is higher (sometimes considerably higher) than expected, because your insurer provided lower coverage due to the provider’s out-of-network status. Surprise Medical Bills are also sometimes referred to as “Balance Billing” because when the insurer pays the provider the lower, out-of-network amount, the provider looks to the patient to pay the rest by sending them a bill for the balance of the amount charged.

Surprise Billing occurs primarily in two circumstances: 1) when an insured patient receives emergency care either at an out-of-network facility or from an out-of-network provider working in an in-network facility or 2) when a patient receives elective non-emergency care at an in-network facility but is treated by an out-of-network health care provider that they did not choose. One common scenario is having surgery done by an in-network provider at an in-network hospital, but the anesthesiologist turns out not to be in-network or having an in-network provider do a medical test that is then sent to an out-ofnetwork lab. Since the insurer does not have a contract with the out-of-network facility, provider or lab, it may decide not to pay the entire bill. In that case, the out-of-network facility or provider may bill the patient for the balance of the bill. These are all considered to be Surprise Medical Bills. A bill for your co-insurance obligation, or a bill for the higher out-of-network amount if you knowingly choose out-of-network care is known as Balance Billing but is not considered a “surprise” bill.

Both federal and New Jersey state law have protections against Surprise Medical Bills or inadvertent out-of-network charges for emergency and non-emergency services. The most crucial difference between the federal and state law is that the federal No Surprises Act, enacted in 2020 and effective as of January 1, 2022, applies to almost all health insurance policies, while the New Jersey law, The Out-of-Network Consumer Protection, Transparency, Cost Containment, and Accountability Act, enacted in 2018, applies only to insurance policies that are governed by New Jersey law and only to the extent that the state law provides protection beyond that provided by the federal law. State-regulated plans include those sold on the Affordable Care Act’s individual and small-group marketplaces, the State Health Benefits and School Employees Health Benefits Plan and fully-insured employer-sponsored plans. They do not include employersponsored plans that are self-insured, meaning the employer’s money is used to pay claims and an insurance company simply administers the coverage. These plans are governed solely by federal law.

Neither the federal nor the state out-of-network law applies to Medicare (including Medicare Advantage), or New Jersey Family Care/Medicaid (including Medicaid managed care plans), the Indian Health Service, Veterans Health Care, and insurance programs that make up TRICARE, all of which generally prohibit balance billing with some limited exceptions. If the state law is more protective of consumers than the federal law, its requirement prevails with respect to plans regulated by New Jersey, so if you are a member of a state-regulated plan, you can look to the state law as well as the federal law for protection. Though it should be noted that the claims processing and arbitration provisions of the New Jersey law apply only when the out-of-network services are by a New Jersey licensed provider in a New Jersey health care facility (with a limited exception for laboratory tests sent out of state for analysis). They do not apply if you have a New Jersey regulated plan, but received services out of the state. In those situations, only the federal law applies.

You cannot waive your rights under either law. This means that you can only lose the protection against balance billing in a non-emergency situation if you make a deliberate decision to receive services from an out-of-network provider, and sign a document saying that. If a provider discloses their out-of-network status to you just at the time of service and has you sign a consent to receive their services without noting in writing that they are an out-of-network provider, that is not sufficient. Under New Jersey law, you must receive notice of the providers’ out-of-network status at the time you schedule the appointment; not the day you show up. Under federal law, you must receive notice of out-of-network status at least 72 hours prior to the delivery of services, and at least 3 hours beforehand if you make the appointment the same day as you receive treatment. You also must be given a plain-language written notice, which includes disclosures of applicable billing protections, among other things, and must sign consent forms to receive out-of-network services BEFORE receiving such out-of-network services.

In addition, all New Jersey insurance carriers that provide managed care within a network are required to:

All health care facilities are obligated to put information on their website about billing, in-network status, etc.

A major gap in both the state and federal law is that neither applies to ground ambulance services. The federal law, however, does cover transportation by air ambulances and it applies in New Jersey.

If you believe that you have been wrongly billed by an out-of-network provider that you did not knowingly and deliberately select to treat you, you should immediately call your insurance company and discuss the situation to confirm that you have wrongfully been billed. You also may contact the New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance at:

NJDOBI | How to Request Assistance-Consumer Inquiries and Complaints

Or

Call the Consumer Hotline at 1-800-446-7467.

Visit No Surprises Act | CMS for more information about your rights under federal law.

Visit NJDOBI | Out-of-network Consumer Protections for more information about your rights under state law

It is always important to know the type of plan you have and the specifics of your plan so that you know whether you need to get a referral before you seek medical treatment, whether certain medical services that you desire or that your physician has recommended are covered and/or considered medically necessary, the amount of co-insurance you will be responsible to pay and other questions. But no matter how well you understand your plan, there will be times when your insurance company denies coverage or limits the amount they will pay for your care. If this happens, regardless of what type of plan you have, you have the right to appeal the company’s decision. You have a certain amount of time to do so, which varies with the type of insurance from as little as 60 days to as long as 180 days from the date you receive a “denial” letter. Once you receive the letter, you should call your insurance company as soon as possible and find out the details of the appeal process.

For more detailed information about the appeals process for your particular type of plan, please refer to New Jersey Appleseed’s A New Jersey Guide to Insurance Appeals.

Emergency Rooms at acute care hospitals are required to provide you treatment in an emergency regardless of your insurance status or ability to pay. Under federal law, regardless of whether you have an outstanding bill, a hospital is not allowed to turn you away in an emergency situation, which includes being in labor if you are pregnant. This right to emergency care is required by a federal law known as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act or EMTALA. (It should be noted, that under New Jersey law, an acute care hospital cannot turn you away in a nonemergency situation as well. This requirement is known as Charity Care and is discussed elsewhere in this Chapter and in Chapter 2).

You are at home, on the road or at work and an accident occurs and you or someone in your family is seriously injured or you have a heart attack, stroke or are in a condition that needs immediate treatment. You call 911 and thanks to the federal and state laws discussed above that protect against Surprise Medical Bills, you do not have to worry about out-of-network charges at whatever Emergency Room you go to. Ambulance transport services are a different story, because those Surprise Medical Bill protections do not apply to ground ambulances, only air ambulances. You are at risk of a Surprise Medical Bill for the ambulance ride unless you get lucky and the town from which you are calling 911 provides Emergency Medical Services (EMS) or emergency ambulance transport and has agreed not to Balance Bill any insured patient beyond co-pays or co-insurance, as some towns have done.

If a family member or neighbor is able to transport the “patient” without using ambulance services, they should go to the nearest hospital, hospital satellite emergency room, ambulatory care center, or ambulatory surgical center. Emergency care should not be sought from an urgent care center, because the protections against Surprise Medical Bills do not apply to them. Urgent care centers, which may be able to treat a broken arm or serious burn, are best used to provide routine care to you at your convenience, without an appointment, although they and their physicians are often out-of-network providers. If you are transported to a hospital, satellite emergency room, etc., you are protected whether the hospital is in-network or not; all services rendered under these emergency circumstances are charged to you as if they were provided by an in-network facility and/ or provider. If the facility and/or the provider contest the payment made by your insurer, they are able to file for arbitration. You, the patient will only be responsible for co-pays and co-insurance at in-network rates and will not be involved in such arbitration.

Once you are in a hospital, there will come a time that treatment to address the emergency ends. This can be as short as hours or as long as days. If you were brought to a facility that is not in-network and you still require additional care, you will be asked to either consent to out-ofnetwork billing, or you will be asked to leave the hospital and seek further services at an in-network health care facility. At that point, you should contact the insurance company to find out what inter-facility transport services are in-network, and also to make sure that the facility to which you are being transferred is in-network.

If you receive emergency services in an acute care hospital or a hospital satellite emergency room, you may be eligible for Charity Care even though you are insured. Acute care hospitals provide short-term medical care for sudden illnesses or injuries and typically offer a range of services, including emergency medicine, inpatient care, surgery, diagnostic testing and intensive care. New Jersey has about 72 of them. In contrast, other types of hospitals might focus on longterm care, rehabilitation or specialized areas of medicine such as cancer.

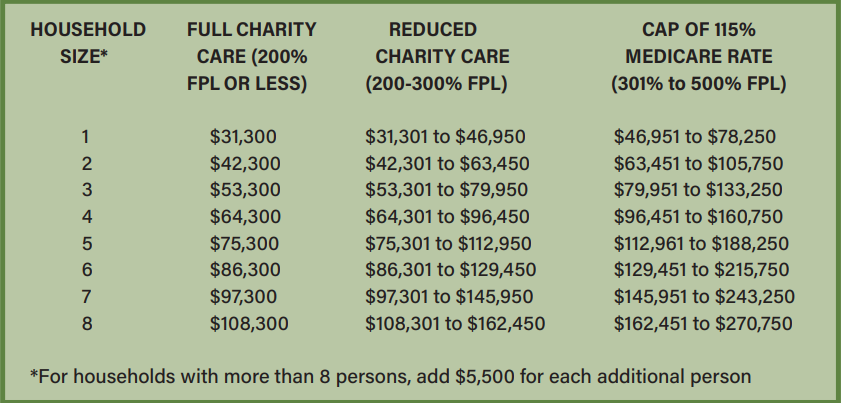

New Jersey mandates that all hospitals provide a 100% discount for residents, regardless of immigration status, with household incomes at or below 200% of the Federal Poverty level or FPL, and discounted care for patients with household incomes between 200% and 300% of the FPL. If you are insured, Charity Care can be used to pay the portion of the hospital bill that your insurer does not pay, including co-pays and co-insurance. To determine if you are eligible for Charity Care, please consult the FPL for the current year since it is adjusted every year. This year’s FPL can be found here.

Because of the Charity Care law, a hospital cannot refuse to provide you care because of an unpaid bill for prior services. Doctors and other providers who treat you outside of a hospital context, however, are free to withhold care because of an outstanding bill.

If you believe you are eligible for Charity Care, do not leave the hospital without an application for it. The hospital is required to inform you of the availability of Charity Care prior to discharge (releasing you after treatment to go home or to another health care facility), and you should ask them about it if they have not done so. You have up to one year (365 days) from the date of service, or 240 days from your first post-discharge bill, to apply for Charity Care, whichever amount of time is greater.

Also, although many physicians providing emergency services at the hospital say that they do not accept Charity Care, New Jersey law requires them to do so. So, if you get a bill from a doctor who treated you on an emergency basis at a hospital and the hospital approved your Charity Care application, the doctor’s bill is invalid, and you can challenge it.

In evaluating your application for Charity Care, the hospital is entitled to ask you for certain documents to prove that you qualify based on your income and assets and also that you are a New Jersey resident, regardless of immigration status. If you do not have the necessary financial documentation, the hospital must accept a certification from you of your household monthly income. A decision on whether you qualify for Charity Care/financial assistance is supposed to be made within 10 days of when the hospital receives the complete application.

A non-profit group called Dollar For might be able to help you with the application process. Their website has a simple, no-cost tool that they say will provide you with a quick answer on whether you are eligible for Charity Care. You input the amount and date of the hospital bill, your household income and size, and whether or not you are insured. If the tool says you qualify, they invite you to fill out their online form and offer to prepare your application and send it to the hospital within 1 to 3 weeks. Once your application is submitted, they say they will email and text you to check in and give you tips on how to follow up and, if necessary, help you submit additional documents and prepare an appeal.

Another possible source of assistance is the Catastrophic Illness in Children Relief Fund (CICRF). It is a state program available to help pay expenses for New Jersey families whose children have an illness or condition where at least part of those expenses are not covered by insurance, State or Federal programs, or other sources.

The assistance is available for any type of illness so long as the costs of dealing with it are “catastrophic” for the family. There is no income requirement but the total amount of eligible medical expenses incurred in any 12-month time period must meet or exceed 10% of the first $100,000 of the family’s income, plus 15% of any additional income over $100,000.

Additional information about the Fund is available on the website and it is discussed at greater length in Chapter 2, Section 4.

You should always call your insurance company to confirm whether both the facility and the physician providing the health service are in-network prior to scheduling care at a hospital, outpatient clinic, or ambulatory care facility owned by a hospital system, whether for preventive care, such as a colonoscopy, or for a surgery, MRI or other procedure. If the procedure requires sedation, you should also ask if about the anesthesiologist too. Even though the hospital and physician you call when scheduling the treatment are required to inform you whether they are in-network, your insurance company is required to maintain a list of in-network providers, and the hospital must list which insurance it accepts on its website, it is always safest to call and speak to an insurance representative to be certain. Websites are often unreliable and out-of-date and you should not rely on them.

Once you have confirmed that the facility and physician performing the surgery or other procedure are in-network, the hospital must provide any ancillary services to you at an in-network level both under New Jersey and federal law. Such ancillary services might include laboratory testing, radiologic imaging and even the food the hospital provides to admitted patients.

You always have the option to select an out-of-network provider. But you will only incur out-of-network charges if you decide to have them after being informed they will cost more and signing a consent form that indicates you want to receive services from this provider even though they are out-of-network. That form must be signed at least 72 hours prior to receiving the services, or at least 3 hours beforehand, if you make the appointment the same day you intend to receive the services.

At the time of scheduling your treatment, you should also determine whether the hospital-owned facility will be charging a facility fee in addition to the bill you will be receiving for medical services. Sometimes health insurance plans do not cover facility fees, or they only cover part of a facility fee. Call the location where you plan to receive care and ask if you will be charged a facility fee. If the answer is “yes,” call your health insurance company to see if they will fully cover this expense. If your insurer will not fully cover a facility fee, ask your physician or insurer to help you find an alternative location that will not charge these added fees

Sometimes, following treatment, you will need additional care or medical equipment. If you are unsure of whether or not you need medical equipment—or if that equipment is covered by your insurance—ask the health care worker who is discharging you to verify if medical equipment and/or follow-up care is necessary as well as its associated out-of-pocket costs. Then speak to your insurance company, and if your coverage is insufficient, ask them for ways you can keep equipment or follow-up care costs to a minimum.

For any care that is scheduled in advance—like an endoscopy, X-ray or non-emergency surgery—you may also ask your health insurance company to provide an estimate of what you will owe. This is referred to as an “Advance Explanation of Benefits.” The plan may provide this estimate in writing, but they are not required to do so. If you get an estimate, be sure to compare it with the Explanation of Benefits (EOB) that you will receive after you receive your scheduled care. Ask your insurance plan to explain anything that does not match up.

In addition, under the Federal Hospital Price Transparency final rule implementing Section 2718(e) of the Public Health Service Act, every hospital operating in the United States is required to provide clear, accessible pricing information on their website regarding the items and services they provide (1) as a comprehensive machine-readable file; and (2) in a display of shop-able services in a consumer-friendly format. Such information may also be helpful to you when deciding in which facility you will have your treatment. Additional information is available at Federal Hospital Price Transparency FAQ.

Because you are receiving care at a hospital-owned facility, you may be eligible for Charity Care even though you are insured. New Jersey mandates that all acute care hospitals, whether nonprofit or for-profit, provide a 100% discount for residents with incomes at or below 200% of the FPL, and discounted care for patients with incomes between 200% and 300% of the FPL. If insured, Charity Care can be used to pay the portion of the hospital bill that your insurer does not pay, including co-pays and co-insurance.

For some people, medical care consists of annual check-ups with a primary care physician and/or gynecologist, and occasional referrals for preventive or diagnostic tests. For others, with chronic diseases or mental health issues, scheduling an appointment with a physician, psychologist or specialist is much more routine and occurs more often.

As we discussed earlier in this Chapter, it is as important in scheduling doctor appointments as it is for arranging hospital care to understand your health insurance policy, what is covered and what is not and the extent of coverage and, correspondingly, what share of the cost you will be expected to pay in the form of deductibles, co-pays and co-insurance. You must also be aware of when referrals and pre-authorizations are needed and ALWAYS check to be sure that a provider is in-network so that you do not end up responsible for costs that you thought were covered or with a Surprise Medical Bill. The provider is required to let you know of their innetwork or out-of-network status. If they are out-of-network, then they have to ask you to sign a consent form acknowledging that you know they are out-of-network and are willing to receive services from them anyway and at a higher than in-network cost.

If an in-network provider does a blood test, imaging test or other type of test done in their office, they cannot send it to an out-of-network lab for analysis, so in this situation, you need not worry about a Surprise Medical Bill. But if they send you elsewhere to get the blood test or other test done, then you must check beforehand to be sure that where they send you is in-network. You cannot assume that anywhere an in-network doctor sends you will also be in-network. And you should not agree to receive testing or other services from a provider whose network status you do not know.

If you cannot find an in-network provider, which is more likely to happen with mental health services and some specialty areas of practice, ask your insurance company if you can see somebody who is out-of-network at in-network rates. They will try to find a provider for you within a certain distance of where you live. If they do not, they should grant your request. However, if they do deny your request, you can appeal that denial, as discussed above regarding denial of benefits.

Following the provision of services by a health care provider, you will be presented with a bill for your share of the cost, probably at least a co-pay and perhaps some cost-sharing (known as co-insurance) as well, especially if you have not yet met your deductible. They will probably expect you to pay that amount on the spot. You might be tempted to pay it with your credit card. If you do, be aware that your debt becomes credit card debt and is not protected by a recent New Jersey law that prohibits the reporting of medical debt to credit agencies, limits the interest charged on medical debt to no more than 3% and only allows garnishment of your wages to collect a medical debt if you make more than six times the Federal Poverty Level (FPL), which is $93,900 for 2025 (6 x FPL of $15,650).

An additional factor to consider is that you are less likely to be sued for medical debt than for credit card debt. Also, health care providers are often more willing to reduce the amount of a delinquent debt if you can show financial hardship. Once you put the debt on a credit card, you lose those opportunities.

Your doctor might encourage you to sign up for a special credit card to pay for medical bills but be aware that these cards are usually not a good choice for this purpose because they often have high interest rates (though they might lure you in with an initial low rate) or unfavorable terms. You also lose the option of negotiating with your health care provider over the bill and it turns your medical debt into credit card debt, with all the lost protections described above. You should exercise similar caution regarding other forms of medical financing or loans that might be offered by your doctor, hospital or a third-party lender.

Accordingly, if you can pay your co-pay in cash, you should do so, and ask for a bill with respect to any other expected payment.

Without insurance, it can be difficult to get a physician to see or treat you, unless you seek services at the emergency room of an acute care hospital, where they are obligated by law to provide care. Acute care hospitals provide short-term medical care for sudden illnesses or injuries and typically offer a range of services, including emergency medicine, inpatient care, surgery, diagnostic testing and intensive care. New Jersey has about 72 acute care hospitals. In contrast, other types of hospitals might focus on long-term care, rehabilitation or specialized areas of medicine such as cancer.

Still, if you do not have health insurance, there are options available to you in New Jersey, where you may be able to receive affordable or even free health care as a “self-pay” patient—one who pays out-of-pocket, usually because they do not have health insurance.

One option is the system of Federally Qualified Health Centers or FQHCs, which are community-based nonprofit health clinics that provide primary care services to underserved communities. They are funded by the federal government and offer services regardless of ability to pay or immigration status. Services are provided on a sliding fee scale. Located throughout the state, they are listed in the Appendix, with addresses and contact information.

A second option is to seek services at any of New Jersey’s acute care hospitals, which are required to treat patients regardless of their insurance status. New Jersey law (N.J.S.A.26:2H-18.64) states that no hospital shall deny any admission or appropriate service to a patient on the basis of that patient’s ability to pay or source of payment. This includes in-patient and out-patient services and covers necessary medical services. Necessary medical services are health care services that are needed to diagnose or treat an illness, injury, or disease. In practice, some hospitals are more receptive than others to serving self-pay patients. In any event, if you have a health emergency, you can go to a hospital-based emergency room and you are assured of receiving treatment, which may include outpatient treatment. Note that the same is not true for Urgent Care Centers, which are not obligated to provide care.

If you are uninsured or “self-pay” (or are not planning to submit your medical bills to a health insurance company), it can be helpful to know in advance what you will be charged for your medical care. The federal No Surprises Act gives an uninsured patient some important tools to find out what their medical costs will be, before they get treatment.

The law requires health care providers to give patients who ask for it a so-called “Good Faith Estimate” of what the services are expected to cost. You should always ask for an estimate and then keep it in a safe place. This is important because if you decide to undergo treatment with the physician or facility that gives you a Good Faith Estimate, you have certain rights to dispute the actual bill if it is at least $400 higher than the estimate you were given. This is discussed further in Chapter 3.

Health care providers, not just hospitals, must use a form similar to this one to inform you of the expected costs for treatment in writing. The form must include the provider’s name and list the services included in the estimate—including the billing codes for each treatment, medication, laboratory test, or other medical service. It must list a total amount along with an itemized breakdown of what you will owe for each expected service and/or medical treatment. Make sure the estimate contains your name and address in addition to your provider’s name and address, billing codes, and a plain-language explanation of the treatment and the estimated price you are expected to pay.

Although you may also request that your physician include in their estimate all ancillary services associated with the treatment, they are not required to do so. Rather, you will likely need to ask for a separate Good Faith Estimate from each doctor and each health care facility to better understand the entire expense of your expected care.

Remember that a Good Faith Estimate is not a contract and does not obligate you to use those doctors and/or hospitals. It is also important to note that you can ask your doctors and hospitals for a Good Faith Estimate at any time—even if you are not ready to schedule your treatment. On the other hand, the physician must provide you with the Good Faith Estimate, in writing, within one business day after your request, if the care scheduled is within the next three to nine days; and within three business days, if the care is scheduled for within the next 10 days. If the Good Faith Estimate is provided electronically, it must be supplied in a form that can be printed and saved. If you delay your care for more than a month, check back in with that provider to make sure the Good Faith Estimate is still accurate.

Note that the Hospital Transparency Rule, 45 C.F.R. Part 180, which took effect in 2021, requires hospitals to post their prices online so before you even request a Good Faith Estimate from one or more hospitals, it should be possible to “shop around” to finds a hospital that charges less for the procedure in question. The NJ Hospital Price Compare website might be able to help you with the price checking process. But never rely on it alone and always request a Good Faith Estimate.

Complaint Line—If you do not receive the Good Faith Estimate to which you are entitled by law, contact the federal government’s No Surprises Help Desk online or call 1-800-985-3059.

Knowing whether you are eligible for financial assistance or insurance is crucial in getting an idea of what anticipated medical care will cost you. If you decide to have treatment at an acute care hospital, at any time prior to your appointment you may also ask to be screened for New Jersey’s financial assistance program (i.e., Charity Care, discussed more fully in Chapter 1 and in Section 4 of this Chapter) or public health insurance coverage, such as Medicaid: Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid or Aged, Blind & Disabled (ABD) Medicaid; Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP), which covers children 18 years or younger in households with income 355% of the Federal Poverty level (FPL) or less, regardless of immigration status; or any program focused on a subsection of the population, such as pregnant women.

Here is a link to the 2025 financial eligibility levels for all (actually, almost all) Medicaid and CHIP programs in New Jersey, both of which are known as New Jersey FamilyCare

You can try to negotiate a reduction in the cost of non-emergency medical care either before or after you receive it. A New Jersey law effective in July 2025 will require health care providers to offer you a Reasonable Payment Plan after you have received care but there is no requirement that providers negotiate with you ahead of time, before they provide health services. That makes it a bit trickier to do ahead of time and some might not be willing to do so.

But you still might want to try, especially for an elective or nonemergency procedure, where you might not be willing to go ahead unless you can negotiate a lower, more affordable cost in advance. If you do try to negotiate, a good starting point is 115% of the rate paid by Medicare, which is the discounted rate that an acute care hospital must charge a patient whose income is 500% of the FPL or less. Section 4 below tells you how to find out what those rates are.

Note that under federal law, Emergency Rooms are required to provide you treatment in an emergency regardless of your insurance status or ability to pay. This right to emergency care under federal law is granted under a law known as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act or EMTALA. In New Jersey, however, your right to care regardless of ability to pay extends beyond emergency situations. As stated above, New Jersey law states that no hospital shall deny any admission or appropriate service to a patient on the basis of that patient’s ability to pay or the source of payment, which includes necessary in-patient and out-patient medical services.

When you receive health care services at a New Jersey acute care hospital (There are currently 72 of them and they are listed in the Appendix), you may qualify for the New Jersey Hospital Care Assistance Program, commonly referred to as “Charity Care.” This financial assistance program addresses how medical care received in a hospital is paid for once the patient has been treated.

The N.J. Health Care Reform Act of 1992, which contains the statutory basis for the Charity Care program, includes a powerful provision that guarantees access to hospital services regardless of ability to pay: “No hospital shall deny any admission or appropriate service to a patient on the basis of that patient’s ability to pay or source of payment.” N.J.S.A. 26:2H-18-64. This provision applies to both for-profit and non-profit hospitals, and hospitals can incur a civil penalty of $10,000 for each violation. Who is eligible for free or reduced rate care under the program, what documentation of income must be produced when applying for such a program, and which services are covered are discussed below.

Eligibility for Charity Care is based in the first instance on income level. A person is eligible for “full” Charity Care (basically free care) if their individual income (or family income, if applicable) is less than or equal to 200 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL).9 A person is eligible for “reduced charge” Charity Care if their applicable individual or family income is between 200 and 300 % of the FPL. The percentage of hospital charges paid by persons in this category is based on a sliding scale that depends on income: persons at 200 to 225% of the FPL pay 20% of the charges, while those between 225 to 250% pay 40%, those between 250 to 275% pay 60% and those between 275 and 300 percent of FPL pay 80 percent of charges, and persons with incomes greater than 300% of the FPL receive no assistance.

There is also help for those whose incomes are higher than 300% of the FPL but below 500%. Hospitals are prohibited from charging an uninsured person whose family income is less than 500% of the FPL more than 115% of the Medicare reimbursement rate. N.J.S.A. 26:2H-12:52.

FPL & Medicare Rate Reference Links

The 2025 Federal Poverty Level is available at this website.

To find out what the Medicare rate is for a particular health service, here is a link to the website that contains that Search tool. Note that you will have to click through two screens and once you arrive at the actual Search page, you will need the five-digit CPT (Current Procedural Terminology) Code, also known as HCPCS (Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System), for the particular procedure you want to look up. If you have already received the care in question, the CPT/HCPCS code might appear on the bill. If not, ask the provider or hospital who provided the service, or will provide it. If you are insured, the codes might appear on the Explanation of Benefits the insurance company sends you or you can call the insurer and ask.

Be aware that what appears to be a single procedure might have more than one code that applies to it and you will have to search the Medicare reimbursement rate for each of those codes and add the amounts together.

Although there is no discretion with respect to the amount of income to qualify for the various Charity Care levels, an applicant has some flexibility in trying to qualify by choosing one of three different time periods in which to measure income. Gross annual income can be measured for the full 12 months preceding the date of service, or by income for the prior three months (multiplied by four), or by income in the prior month (multiplied by 12). You may choose whichever of these time periods results in the lowest income so that you can qualify for financial assistance. N.J.A.C. 10:52-11.8(e). This option is important to low-income, uninsured individuals who do not have steady income throughout the year. You need to be aware of this regulation since many hospital administrators are not.

Charity Care applicants also have the option of proving their income by a variety of methods. applicable regulations very sensibly recognize both that there may be a variety of methods to ument income during the relevant period and that some applicants may not be able to prove ome by conventional means, such as a pay-check stub, W-2 form, letter from an employer, ual Social Security statement, etc. The regulations specifically permit an applicant who is e to document his income by conventional means to provide a written attestation (a declaration er penalty of perjury) of income. N.J.A.C. 10:52-11.9(a)(3). This is another important option vided in the Charity Care regulations that hospital administrators may not tell you about.

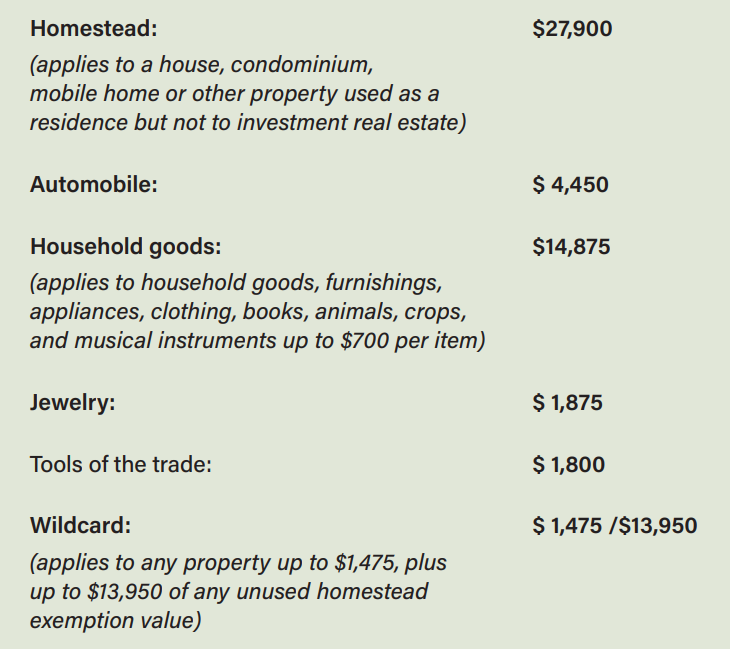

In addition to proving income eligibility, individuals must pass an asset eligibility test. The asset limits are $7,500 for an individual and $15,000 for a family, if applicable. The regulations specify what types of assets are included, basically cash and things that can be easily converted to cash, such as checking accounts, savings accounts, certificates of deposit, corporate stock, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) and equity in real estate, except that a primary residence is a specifically excluded asset so if you own your home, you can still qualify. N.J.A.C. 10:52-11.1 (c). You must be careful to make sure that a hospital does not take into account assets that you might hold but which either cannot be readily converted into cash or are not actually owned by you but held in trust for a parent or child.

Another important limitation on the asset limits is that an applicant must have an opportunity to try to get below the $15,000 limit by deducting any amounts they have already paid or will pay for medical services, known as “qualified medical expenses,” which are the same kinds of medical expenses you can deduct on your federal income tax return. Most medical expenses—such as doctor visits and prescription drugs—would be included but not most cosmetic procedures and nonprescription drugs. There is a long list on this website, which includes abortion and acupuncture, ambulances, supplies such as bandages and wheelchairs, birth control pills, condoms, pregnancy test kits and vasectomies, Braille reading materials (if you are visually impaired), hearing aids, programs to help you stop smoking (though not nicotine patches or gum or other drugs to help you quit) or lose weight (if it is a treatment for a specific disease diagnosed by a doctor such as obesity or heart disease) and many more health-related expenses.

Here is an example of how meeting the Charity Care asset limit works: A married individual has family income below 200 percent of the FPL, but also $16,000 in a bank account. Assume that the hospital bill is $50,000. Despite appearing to be disqualified because their assets are $1,000 above the limit, they might still qualify if they or their spouse has already incurred uncovered prescription drug or dental expenses during the year that exceed $1,000 or if they agree to pay $1,000 of the $50,000 medical bill.

It is undisputed that “necessary” inpatient and outpatient hospital services are covered by the Charity Care program. The statute that authorizes this is N.J.S.A. 26:2h-18.60(b), which says that a person whose income is less than or equal to 300% of the FPL shall be eligible for charity care for “necessary health care services provided at a hospital.” These include services as varied as advanced life support (ALS) services and outpatient dialysis services. N.J.A.C. 8:31B-4.38. ALS services include pre-hospital services provided by a mobile intensive care unit in an ambulance, which are required to be covered by regulations that are separate from the main Charity Care regulations.

The most controversial and uncertain issue is whether hospital-based services that are provided by doctors but are separately billed by them are covered by Charity Care. For example, a patient who goes to the Emergency Room with chest pain and is hospitalized for a cardiac catheterization may be determined eligible for Charity Care but may nevertheless receive separate bills from the Emergency Room doctor, the radiologist, the anesthesiologist, and even the cardiologist who performs the catheterization. Many people assume that since the bill is not directly from the hospital, the service is not covered by Charity Care, and many physicians who provide such emergency care services in the hospital deny that they are able to bill patients separately. On the other hand, there is a strong argument that allowing the patient to be billed for these medical services that occurred in the hospital would defeat the language and purpose of the Charity Care statute. The statute requires Charity Care to cover income-eligible patients who receive treatment at an acute care facility—treatment that is provided by a physician. Accordingly, not just hospital-employed physicians must provide services on the terms required by Charity Care, but all physicians providing such services at these locations.

If you or a family member receives a bill from an individual physician who provided services to you at an acute care hospital, please contact Legal Services of New Jersey (call their Help Line, which is available Monday to Friday from 8 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., at 888-LSNJ-LAW or 888-576-5529). Or you can seek representation to help challenge the bill from one of the Legal Services offices located throughout the state, as listed in Appendix C.

Individuals obviously cannot apply for Charity Care if they are unaware of the program. Therefore, hospitals have a legal responsibility to make sure that you and other patients are aware of the program, are given an opportunity to apply, and are given an explanation of the reasons if the application is denied. The most fundamental hospital responsibility is to give each patient a written notice of the availability of Charity Care no later than the date that the first bill is sent. However, we recommend that if you are uninsured and believe that you are incomeeligible, you should not wait for the bill but should ask for a Charity Care application prior to being discharged from the hospital or immediately after.

In addition, as mentioned above, you may be eligible for another medical assistance program (such as Medicaid or New Jersey FamilyCare), and the hospital must refer you to the appropriate program within three months of the date of service. These responsibilities of the hospital are enforceable; meaning that if the hospital does not provide written notice of Charity Care availability or make an appropriate referral for another medical assistance program within the applicable time limits, the hospital may not bill you for the service. N.J.A.C. 10:52-11.5(d)(3). This is important for you to raise with the hospital or any person trying to collect the bill on behalf of the hospital, and you should demand a Charity Care application if you have not previously done so

You have the right to submit a Charity Care application to the hospital at any time within a year from the date of the service, and the hospital may extend that period to within two years of the date of service. Indeed, a hospital has an incentive to extend that period to two years, since if you do qualify for Charity Care, the hospital will be reimbursed by the State for that service, while if the hospital does not take the application, it will have to go through the effort of trying to collect from you, even though you might have no ability to pay, even if a judgment is entered against you. The hospital must inform you, the applicant, in writing within 10 days of its decision on your Charity Care application. It must also inform you if you provided insufficient information with the application or of other reasons for denying it.

A non-profit group called Dollar For might be able to help you with the application process. Their website has a simple, no-cost tool that they say will provide you with a quick answer on whether you are eligible for Charity Care. You input the amount and date of the hospital bill, your household income and size, and whether or not you are insured. If the tool says you qualify, they invite you to fill out their online form and offer to prepare your application and send it to the hospital within one to three weeks. Once your application is submitted, they say they will email and text you to check in and give you tips on how to follow up and, if necessary, help you submit additional documents and prepare an appeal.

Another possible source of assistance is the Catastrophic Illness in Children Relief Fund (CICRF). It is a state program available to help pay expenses for New Jersey families whose children have an illness or condition where at least part of those expenses are not covered by insurance, State or Federal programs, or other sources, such as fundraising. The Fund is intended to assist in preserving a family’s ability to cope with the responsibilities which accompany a child’s significant health problems.

The assistance is available for any type of illness so long as the costs of dealing with it are “catastrophic” for the family. There is no income requirement but the total amount of eligible medical expenses incurred in any 12-month time period must meet or exceed 10% of the first $100,000 of the family’s income, plus 15% of any additional income over $100,000. You can apply for multiple 12-month periods and as far back as seven years.

A broad range of medical expenses is covered, including but not limited to: physician care in all settings, therapies, pharmaceuticals, acute or specialized hospital care, medical equipment or disposable medical supplies, medically related home and vehicle modifications and medical transport; home health care; and addiction and mental health services.

You cannot apply for payment of medical expenses in advance but must wait until the medical treatment and services have been provided and then seek reimbursement. In fact, you must submit the Explanation of Benefits in applying for the Fund so it is best to wait until the claims have been processed through insurance. You can apply for claims that have not been paid in full because the Fund will not only reimburse you for expenses paid out of pocket but can pay providers directly for outstanding balances.

Children up to age 21 are covered but reimbursement can be sought for a child older than that if the expenses were incurred while they were still under 22. Undocumented children are not eligible. The assistance is available only for children who are legally domiciled in New Jersey AND are U.S. citizens or green card holders, or who have obtained legal immigration status (i.e., hold visas that allow a family to establish residency).

Additional information is available on the website.

Whether or not you are insured, at some point after you receive health care services that are not fully covered by insurance or by Charity Care, you will receive a bill from the provider or providers involved in your treatment. This Chapter will tell you how to read that bill, how to figure out if it is correct – both with regard to what it is charging you for and how much—and, once you know how much you really owe, how to work out a payment plan with the provider so that you can pay the bill. We will also suggest how to proceed if you cannot agree with the provider on the amount you owe, or if you disagree with a decision by your insurance company to deny coverage or erroneously treat the bill as out-of-network.

First, let’s clear up any confusion between a medical bill from a provider and an Explanation of Benefits from your health insurance company regarding your billed services.

Before you obtain medical care, health providers usually ask you to sign a form assigning your insurance benefits to them. That allows the doctor or other provider to bill the insurance company directly for their services. Most providers will collect your co-pay at the time of the visit and then hold off on further billing until your insurer pays its share. You will then be billed for any shortfall or difference—typically, an amount representing your co-insurance or share of the cost. There might also be some providers who want you to pay them in full at the time of service, leaving you to seek reimbursement in whole or in part from your insurance company.

Whether the insurance company pays the provider directly or reimburses you after you have paid the provider, it should send you what is call an Explanation of Benefits, which informs you about what services were billed, what was the Negotiated Rate for such services (the lower, often much lower, amount that the provider and insurer have negotiated for that particular service), what the insurer paid, what you might have paid already (usually the co-pay collected at the office at the time of service) and any additional amount still owing, which you are expected to pay.

After you have verified the accuracy of the bill and how much you owe, you still might not have the funds on hand to pay it all at once.

Be aware that if you pay a medical bill with a credit card, the medical debt will lose certain legal protections that otherwise apply to it under a 2024 New Jersey law known as the Louisa Carman Medical Debt Relief Act, including a 3% cap on interest and a ban on reporting such debts to credit reporting agencies. The same is true if you use financing services like CareCredit and similar medical payment cards to pay for purely cosmetic procedures, spa services or veterinary services for a pet. Also, be aware that CareCredit and some other types of medical financing might advertise promotional financing with no interest or a very low interest rate over a specific period of time, but if you fail to fully repay within that time or miss a payment, the interest might be applied and possibly at a higher rate than would ordinarily be charged. You should exercise similar caution regarding other forms of medical financing or loans that might be offered by your doctor, hospital or a third-party lender.

If it is possible for you, you might want to find some other way to pay a medical bill, such as by entering into an installment plan (discussed below) or borrowing the money from a relative or friend.

Some providers currently offer payment plans. For example, Summit Medical Group, which has thousands of providers in a variety of medical specialties in five states with 170 locations in New Jersey, offers two-month interest-free payment plans when you pay through their online portal. If you need more time than that, they provide a phone number you can call to negotiate a longer time, though they might then charge interest.

Now, all health providers in New Jersey are required to offer a “Reasonable Payment Plan” as a result of a state law which took effect on July 22, 2025. All health care providers, including private physicians, must offer such a plan before they can start medical debt collection efforts. (Debt collector agencies are also subject to this requirement and cannot sue you prior to offering you a Reasonable Payment Plan.) These Payment Plans can last from six months to five years, possibly even longer, based on how much you owe and your ability to pay. The amount of the monthly payments cannot be greater than 3% of your individual monthly income, if known to the provider or debt collector, and the annual interest rate cannot be more than 3%.

The Payment Plan requirement extends to both insured and uninsured patients. If you are insured, the amount of the bill will depend on whether you have met your deductible, and whether your health plan requires you to pay a percentage of the charge your insurer has negotiated for the services you received. If you are uninsured, there is no prior negotiated rate and you will almost certainly be charged a higher amount than someone who is insured. Therefore, before the provider offers you a Payment Plan, you want to first try to lower the amount of the bill. Here are some possible ways to do that

If the bill is from a hospital, they are not allowed to charge you for any services unless they first determine whether or not you are eligible for Medicaid or Charity Care, which is discussed above in Chapter 2, Section 4. If they have not done that and you think you might be eligible, you can insist that they make that determination first. You may have to prove your income using pay stubs, and/or information about government benefits, although hospitals are required to accept your certification of your monthly income if you are not employed or cannot provide certain documents.

It is possible that you need not pay any portion of a hospital bill. Even if your income is a little too high to qualify for Medicaid or Charity Care, you might still be entitled to financial assistance if your household income is below 300% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). And if your household income is below 500% of the FPL, you get a discounted rate, which is $115% of the rate paid by Medicare, which tends to be even lower than the rate negotiated by private health insurance companies. For additional information about Charity Care, including a chart showing levels of income eligibility, see Chapter 2, Section 4.

In any case, make sure before you pay or agree to a payment plan, that you are getting any financial assistance to which you might be entitled. If you qualify for a reduced rate, that lower rate should apply to every portion of the hospital bill, including the services of every doctor who treated you there, even if they are not hospital employees. This is important to know, since physicians providing services at a hospital typically do not accept Charity Care; however, under New Jersey law, if you qualify for Charity Care and received services at a hospital on an emergency or non-emergency basis, any physician who treated you at the hospital must accept reimbursement at Charity Care levels, with you paying nothing or only a percentage.

Even if you do not qualify for Charity Care or financial assistance, do not just enter into a Payment Plan based on the full amount. You can still try to reduce the size of the bill by asking the hospital or health care provider if they will accept a lower amount. Hospitals and doctors might be open to this because they would rather not have to turn to debt collectors or lawsuits to collect from you. Start by suggesting that you pay the Medicare rate for the service or procedure. Medicare rates are available at this website with its Physician Fee Schedule Look-up Tool, but they can be tricky to access because you need the five-digit Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code, also known as the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code, for the particular service or procedure. Doctors use those codes to bill insurance companies and seek prior approval for health services and procedures so you can try to obtain the HCPCS/CPT codes from your provider or insurance company.

If you are unable to determine the Medicare rate because you do not have the HCPCS/CPT code or codes, then a general rule of thumb is that it is about 20% of the full charged rate. So, you should offer to pay 20% of the amount billed and make clear that it is because that is about what Medicare pays. If the provider refuses, do not give up right away but continue to try to negotiate and hopefully still arrive at an amount less than the original bill.

The Appendix contains a template for a letter you can write to your provider or hospital in trying to negotiate a Payment Plan.

If you are insured but have a large deductible or co-pay to satisfy, you can also try to negotiate a reduction before entering into a Payment Plan. Because the insurance company already negotiated a reduced rate, and you are not dealing with the full charged rate, however, any possible reduction would be much smaller.

Hopefully, insured or uninsured, you will get the amount reduced and the Payment Plan will be based on that lower amount. The law requires that the monthly Payment Plans are an amount that you can reasonably afford and the payments are generally supposed to be stretched out from six months to as long as five years based on your income and the amount of the debt.

As stated above, the monthly payment cannot exceed 3% of your monthly income but only if the provider or debt collector trying to collect the debt knows that information. If it is a hospital, you might have told them your household income so they could determine if you qualified for Charity Care/financial assistance. But remember, unlike Charity Care, which is based on household income, the Payment Plan will be based on the patient’s individual monthly income. If you have not given the hospital or provider the relevant information, and you are offered a Payment Plan calling for a monthly payment higher than 3% of your monthly income, you can argue that the plan is not “reasonable” under the law, but you will then have to provide your financial information so they can calculate the amount that IS 3% of your monthly income. Before you provide the hospital or physician with information about your income, you should make sure that they will keep the information confidential.

Under the Louisa Carman Medical Debt Relief Act, the Payment Plan has to be in writing and state the total amount owed, the total monthly payment, the payment schedule and the interest. Even after you accept the plan and start making payments, if there is a significant change in your finances—such as loss of a job or reduced hours—the monthly payments and the length of the plan can be adjusted.

Remember, mark the due date for your first payment on your calendar to help you remember to send your payment on time. Late fees may be charged otherwise, but if you miss a payment, the provider has to give you a 60-day grace period.

You might not be able to agree to the Payment Plan offered by the health care facility or provider because you believe that the bill is inaccurate, which is not uncommon with medical bills. You should first contact the billing department of the hospital or provider to try to clear up the error but if that fails, you will need to take further action.

If you are insured, please discuss this issue with your insurance company by calling the phone number on the back of the card and asking for the fraud department to dispute the bill. If you did not receive the services that are being billed, if the bill is duplicative of a bill that you already paid, if the provider “up-coded” the services that you received (by billing for something more expensive) or you received an out-of-network bill when you did not deliberately decide to be treated by an out-of-network doctor (i.e., a Surprise Medical Bill), you should report these issues to your insurer. The insurer is best able to understand the situation, confirm if you are correct and will advise you how to proceed.

The New Jersey Department of Banking and Insurance (DOBI) is responsible for implementing the No Surprises Act in New Jersey and for coordinating complaints against insurers, hospitals and physicians under the state’s own Out-of-Network law, so they are the place to complain to about a Surprise Medical Bill, under both state and federal law.

You may file a complaint with DOBI by calling the general number, 609-292-7272, or its Consumer Hotline, 800-446-7467, which is staffed Monday to Friday, from 8:30 am to 5 pm. Alternatively, you can mail a written complaint to DOBI’s Consumer Inquiry and Response Center, P.O. Box 471, Trenton, NJ 08625-0471, or file one online.

If you are covered under a Managed Care plan (either HMO or PPO), DOBI has an office within Consumer Protection Services that handles complaints from consumers regarding coverage and payments under the plan. If your complaint has more to do with the insurance company than the provider, you can call 888-393-1062, fax 609-777-0508 or 609-292-2431, or write to:

Office of Managed Care

Consumer Protection Services

Department of Banking and Insurance

PO Box 475

Trenton, NJ 08625-0475

Additional information about filing a complaint is available here.

If you are a Medicare patient, you can call 800-MEDICARE or 800-633-4227, where help is available 24/7 except for some federal holidays. TTY users can call 877-486-2048. However, if the issue involves a denial by the insurer of coverage for the services you received, or any part of them, you should file an appeal with the insurance company. This type of appeal, known as an internal appeal, must be filed within a certain time after you receive notice of the denial of benefits depending on the type of insurance you have, and each insurer has its own process. The appeal process should be set forth clearly on the insurer’s website and in its benefits manual. For further assistance on how to appeal, please refer to New Jersey Appleseed’s A New Jersey Guide to Insurance Appeals.

Once your insurer makes a final decision, DOBI provides a way to appeal that denial of coverage through the Independent Health Care Appeals Program. It provides independent external reviews of adverse benefit determinations, including denials of requested services and/ or reimbursement of services as not medically necessary, as experimental or investigational or as cosmetic. Your right to this appeal is mandated by the New Jersey Health Care Quality Act, N.J.S.A. 26:2S-11 and N.J.S.A. 26:2S-12. There is a $25 fee for the appeal, which you need not pay if you win the appeal or show that you are on Medicaid NJ FamilyCare, General Assistance, Supplemental Social Security, NJ Unemployment Assistance or Pharmaceutical Assistance to the Aged and Disabled (PAAD).

Please note that if you do file an appeal with your insurer, and then through the state Independent Health Care Appeals Program, neither the health care provider nor any debt collector is allowed to communicate with you about that debt or try to collect it as long as the appeal is pending or underway. This only applies, however, if they know about the appeal so you should make it a point to let them know about it, preferably before they start to try to collect but certainly once they do start and they will be required to stop until the appeal is decided.

If you are uninsured and think you’ve been sent a bill that you should not have to pay, you can file a complaint with the New Jersey Attorney General’s Division of Consumer Affairs or consult a lawyer at one of the Legal Services offices located throughout the state, as listed in Appendix C. Either should be able to advise you on how to proceed (i.e., suggest an action plan) once they understand your individual circumstances and reasons for believing that you should not have to pay.

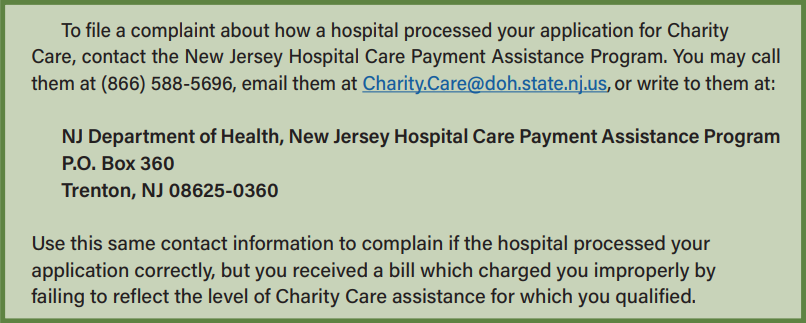

If you were approved for charity care, financial assistance or a discounted rate, and the bill does not reflect that approval, file a complaint with the New Jersey Hospital Care Payment Assistance Program. Call them at (866) 588-5696, email them at Charity.Care@doh.state.nj.us, or write to them at:

NJ Department of Health, New Jersey Hospital Care Payment Assistance Program

P.O. Box 360

Trenton, NJ 08625-0360

If the bill that you seek to dispute is $400 or more than the Good Faith Estimate you previously received, proceed as follows:

In general, if you are either insured or uninsured and want to learn more about your rights to dispute a Surprise Medical Bill you can do so at the website of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and/or by calling the No Surprises Help Desk at 800-985-3059. The Desk is available 7 days a week, from 8 am to 8 pm on weekdays and from 10 am to 6 pm on weekends and assistance is offered in many languages, including Spanish, French, Arabic and Russian. They can also provide resources in large print, Braille and audio.

If your medical bill goes unpaid beyond its due date and if you are unable to negotiate a reasonable payment plan or you are challenging the accuracy of a medical bill, contesting the denial of benefits or the level of benefits paid by your insurance company, or simply can’t afford to pay the bill, the provider might send the bill to a collection agent, or sell your debt to a debt collection company which will try to get you to pay and sue you if you are not able to do so. Here is what you should know going forward.

As a general rule, if you fail to pay your bills, your failure to pay can be reported to a credit reporting agency and hurt your credit score. People with a low credit score can have difficulty renting an apartment, or buying a car or a house, or obtaining a loan. In some cases, a low score can even keep you from getting a job if the employer does a credit check before hiring.

In 2023, the three major credit bureaus, Equifax, Trans Union, and Experian, removed medical debt under $500 from credit reports and on January 7, 2025, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau finalized a new federal rule that bans reporting medical debt of any amount on credit reports and prohibits lenders from using medical information in making loan decisions. As of Spring 2025, the rule was scheduled to take effect on June 15, 2025, but its future is uncertain because it is being challenged in court and the Trump Administration will probably not defend it.